The Gurdjieff Work, Boris Mouravieff’s Gnosis and Robin Amis

BY MATTHEW SUTTON

An article on how Gnosis in English came to be (and more), by Matthew Sutton

Copyright 2025 by Matthew Sutton and Praxis Research Institute, Inc.

Introduction

This article describes events, over thirty years ago, surrounding the discovery, translation, and publication into English of Gnosis: Study and Commentary on the Esoteric Tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy by the émigré historian Boris Mouravieff. Mouravieff himself has gained a reputation in the wider circles of the Gurdjieff Work because he claimed that his book, written over three volumes, gave a more complete version of the teaching brought by G.I. Gurdjieff and his pupil P.D. Ouspensky. The fact that he further claimed that these teachings had their origin in Eastern Orthodoxy was, on the whole, met with scepticism in the English-speaking world when Robin Amis, the translator of these volumes in English, published and promoted them in the 1990s. While some authorities were open-minded to Mouravieff’s claims, others, notably the writer William Patterson, were not. His book, Taking with the Left Hand, accused Mouravieff of deceit, plagiarising Ouspensky's book, In Search of the Miraculous, and reframing it as Eastern Orthodoxy. In this enterprise, he framed Robin Amis as the enabler. For the mainstream Fourth Way audience, Patterson’s accusation, his dismissal of Mouravieff’s work, and Robin Amis’s refusal to respond to the criticism set the tone for all future discussion around Mouravieff’s work in relation to the teachings of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, as well as the latter’s relation to Eastern Orthodoxy. The problem is, as we will show in a series of articles of which this is the first, there is a much firmer basis for Robin Amis’s views on Mouravieff and the connection to Eastern Orthodoxy than is currently appreciated by those in The Work. This first article will show that Patterson's book was poorly researched and ill-informed, leaving much of his argument based on his own personal opinion. These opinions have influenced later commentators and writers, leaving certain key aspects of the origin, history, substance, and context of Gurdjieff’s teaching unknown and unappreciated. At best, this has diminished the richness of the teaching; at worst, it has created an unnecessary roadblock for future seekers and researchers of these important subjects. The overall aim, then, in writing these articles is to reopen this exploration and discover new opportunities for research into the origins of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky’s pioneering work and its connection to Eastern Orthodoxy.

Part I

I first came across Gnosis 1 in a Waterstones bookshop in London in early 1992. At that time, I had read some of Gurdjieff’s works and was actively studying Ouspensky's books, such as A Record of Meetings and The Fourth Way. I had also recently joined a “Fourth Way” group and been introduced to “The Work”2, a means of spiritual development while living an ordinary life in the world. As a young man in my late 20s, I wanted to discover my life's true purpose and what I should be doing with it, and “The Work” offered many interesting ideas and perspectives. Gnosis brought these ideas together in a very succinct way. It defined a method and way to approach life in a far more objective way. It provided perspective, and while books such as The Fourth Way introduced the need to work on oneself, Gnosis provided all of that but also gave a point of orientation as well as a context.

Gnosis also claimed to be a study of the “esoteric tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy”. This gave an unusual impression because, though it claimed a Christian basis, the language conveyed in Gnosis reflected that of The Work and not one easily identifiable as having a Christian basis. Though having read Ouspensky’s A New Model of the Universe and Maurice Nicoll’s The Mark, I had already come to understand that the Christianity we see today, especially in the West, must be very far from the original teachings of Christ and the experience of the Apostles. For this reason, I remained with an open mind as to the truth or otherwise of Mouravieff’s claim. Furthermore, I had a profound conviction that this teaching still had to exist and could be found. As a result of a series of coincidences, I came to understand something of this mystery, having been invited to attend the Divine Liturgy at the Russian Orthodox Cathedral at Ennismore Gardens. At that time, the liturgy was regularly officiated by Metropolitan Anthony, who also lived there and was an immense presence and guide to the many who, like me, first met Orthodoxy through the beauty of the church, its art, and the sung harmonies. Yet despite this discovery and my later baptism into the Orthodox faith, it was also clear to me that as an imperfect human being, I had a long way to go to realise my desire to become truly Christian. For this reason, Gnosis never left me, and it became a reference and orientation point, a comprehensive manual for "one who works in the world."

Before all this and a short time after I first bought Gnosis, I discovered I lived only a short distance from Martin Gordon, who was responsible for the typesetting and selling of the books in the UK. Martin was a Study Society member and a former student of Robin Amis, a former teacher of Ouspensky’s ideas who had coordinated the translation and publication of the books. The first two volumes had been completed, and Volume 3 was being translated and edited. Robin was living in Massachusetts, and I offered my services to help Martin's attempts to publicize it in the UK. This work, done voluntarily, involved visiting bookshops, book fairs, and arranging talks. Through these efforts, I began to meet some of the people working with Robin, as well as former pupils of both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky who were still alive and had taken an interest in bringing Gnosis to public attention. For me, as a young man, this role felt like a great honour, and I took on the opportunity with open arms.

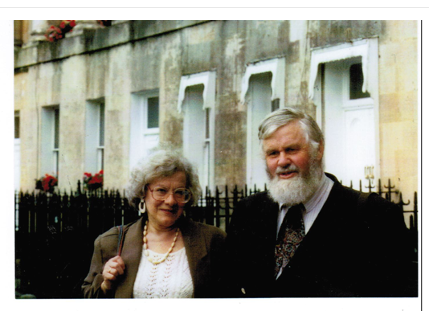

Robin was something of an imposing figure. Though we had corresponded, my first meeting with him was at the Royal Overseas League on Haymarket in the lounge room overlooking Green Park. He was clearly happy for me to offer my services, and we began a regular correspondence, but how he could help me in my spiritual search was much less clear. It was only when I travelled to Massachusetts in the winter of 1993 and met Lillian, Robin’s wife3, and their small study group that things began to make more sense. As I came to know, Lillian possessed an extraordinary asset, and that was a heart of immense proportion and capacity. She had a wonderful ability to weigh the facts of a situation and return with a penetrating question or summary that always touched the heart of the matter. She was an excellent judge of any situation and the human character. It became clear to me over the years that I knew them, that Robin and Lillian were “cut from the same cloth”. Her heart and his immense intellect were perfectly matched. Where she was able to soften him, he was able to enlighten her. In their Massachusetts house in the cold of that icy winter, I came to understand the nature and depth of their work, undertaken at great personal sacrifice.

Robin had met "The Work" in 1950s London in the period after Gurdjieff and Ouspensky's death. He had joined the Colet House group run by Francis Roles, one of Ouspensky's senior pupils, and proved himself as a capable group leader. By the mid-1960s, he had started “The Society of the Inner Life,” 4 was running several groups in the Home Counties and the West Country. During the 1970s, group work had developed and was centred in the Cotswolds at Wetherall House. Robin and Lillian had met and married and the craft workshops they ran were part-funded by the Arts Council. They received national recognition for their artistic achievements, most notably for large-scale tapestries which were created by group members applying principles of The Work, such as working with attention and self-remembering. Then in the late 1970s, Robin took senior members of his group to see a talk by Metropolitan Anthony, then bishop of the Russian Cathedral at Ennismore Gardens. This event, combined with the financial demise of Wetherall due to cost-cutting by the Arts Council, had a profound effect on Robin. So began a journey that took him away from The Study Society and into a lifelong study of the ancient tradition of spirituality that has been preserved and practiced on Mount Athos and other Orthodox monasteries like it, since at least the fourth century.

Though Robin had embarked on a path towards Orthodoxy, The Work and those associated with it continued to appear on his journey. On Robin's first visit to Athos, he met Gerald Palmer, a former pupil of Ouspensky who was also staying at Grigoriou, one of the 20 major monasteries on the Holy Mountain. This was in 1982, just two years before Palmer’s death. Palmer himself had been instrumental in introducing the spiritual tradition of Mount Athos to the West by helping to translate and publish, along with Evgenia Kadloubovsky, several key texts from the Russian Philokalia into English. Palmer later teamed up with Philip Sherrard and Timothy Ware (later Bishop Kallistos Ware) to work on the translation of the complete Greek text following the death of Kadloubovsky.

The Philokalia is a 5-volume collection of works that was originally compiled in the 18th century by Nicodemus the Hagiorite and Macarius of Corinth. Subsequent translations were followed into Slavonic by Paisius Velichkovsky, and a complete Russian translation was prepared by Theophan the Recluse in the 19th century. These translations had a profound effect on the spiritual and cultural renaissance experienced by the Orthodox East, especially Russia. The Philokalia is essentially a compendium of the spiritual wisdom of the masters of the Hesychast tradition from the 4th century to the 15th century. For Western seekers, the perfect introduction to the Philokalia and how to approach it can be found in the spiritual classic The Way of a Pilgrim. This short, highly readable book follows the trials and tribulations of an unknown seeker on his journey through 19th-century Russia in search of an elder or master who can teach him the secrets of the Jesus Prayer. This prayer, used in repetition, forms the basis for the spiritual discipline required to begin the practice of Hesychasm, that sublime way that leads to stillness of the heart.

In the early years of the 1980s, both Robin and Lillian were received into the Orthodox Church by Bishop Kallistos Ware, who was also his confessor, and Robin founded Praxis Institute Press. Initially, the press was established to publish key Orthodox works, and it translated and published several texts, working with Esther Williams as translator, most notably The Heart of Salvation by Theophan the Recluse. It also produced an audiotape of readings from the Philokalia, chosen by Gerald Palmer for his blind friend Julian Allen and read by Sergie. There were also two series of talks by the then-abbot of Grigoriou monastery, Father George Capsanis. Like Palmer before him, Robin maintained his close connection with Grigoriou, visiting close to 60 times up to his death in 2014.

Robin visited Palmer at his home in Newbury and knew he had been a student of Ouspensky, but Palmer never spoke of his background. The knowledge of that relationship came later when Robin and Lillian were living at Avening House and had joined the Greek Orthodox Church in Bristol. By another coincidence, two of the parishioners there were Sergei and Leslie Kadloubovsky (Kadleigh). Sergei was the son of Ouspensky's secretary, Evgenia Kadloubovsky, and he had grown up in Ouspensky's household at Lyne Place during the 1930s and 40s. It was Sergei who related the story that it was Ouspensky who had asked Madame Kadloubovsky to assist in the translation of sections of the Russian Philokalia for group meetings. Palmer had also helped in this task, and it was this undertaking that had awakened his interest in Orthodoxy, especially the Jesus Prayer. Following Ouspensky’s death, Madame Kadloubovsky encouraged Palmer to visit Athos and specifically Father Nikon Strandtman, a monk and a friend of the Kadloubovsky family from pre-revolutionary Russia. In the event, they met only by chance because Father Nikon had only just come out of years of seclusion, and Palmer was the first person he saw on his arrival. Subsequently, he became Palmer’s spiritual father and, on his advice, took it in hand, along with Mrs Kadloubovsky, to translate an anthology of works from the Philokalia. Entitled Writings from the Philokalia on Prayer of the Heart, the book was published by Faber and Faber on the recommendation of T.S. Eliot in 1951.5

Ouspensky's own appreciation of the Orthodox spiritual tradition and the Jesus Prayer is known to students of Ouspensky's earlier works, for example, his chapter in

A New Model of the Universe, “Christianity and the New Testament,” as well as his introductory lectures, The

Psychology and Cosmology of Man’s Possible Evolution. However, less well known was the fact that Ouspensky, who was an Orthodox Christian by birth, regularly attended the Liturgy up to his death.6

Robin used to tell me this, and did so with some amusement, because no one else knew it. Though he never told me his source, as I learnt more about Sergie, who, as Madame Kadloubovsky’s son, grew up in the Ouspensky household, I surmised only he could have known. It painted a picture of an intensely private man who completely separated his life from those of his students as he did Orthodoxy from his professional life in The Work. Robin also always maintained that in pre-revolutionary days, Ouspensky, along with Madame Kadloubovsky, had also been friends with Father Nikon. More recent research suggests that the common link might have been membership of the St Petersburg branch of the Theosophical Society, of which Father Nikon was for a short time a member,

7 and this may also have included Mouravieff.

8

Part II

In the late 1980s, Robin suffered a back problem and visited an osteopath in Cheltenham. During one visit, the osteopath asked Robin about his interests. Robin spoke about his research and visits to Mount Athos. Hearing this, the osteopath mentioned that another of his patients had the same interest and was engaged in the translation of an important text relating to Eastern Orthodoxy. This text turned out to be Boris Mouravieff's Gnosis, and the gentleman in question was Sadek ‘Dick’ Wissa, an Egyptian who was living in England. He was under the direction of Doctor Fouad Ramez, a former student and correspondent of Mouravieff who lived in Cairo. Robin and Lillian took the opportunity to meet with Dick as they both realised that coincidences of this nature go beyond chance, indeed, as Gerald Palmer himself once stated, “in the spiritual life there is no such thing as mere coincidence”.9 A warm friendship ensued between them, and as a result, a collaboration was struck up in the efforts to complete the translation. For Sergie, it also began to answer questions about the mysterious "third man" that used to visit Lyne during the 1930s.

Over the next five years, all three volumes of

Gnosis were translated and published. Dick, Robin, and Lillian coordinated the translation and editing work, closely assisted by Sergei and Leslie. Robin also corresponded with and, on one occasion, visited Dr. Ramez in Egypt.

It was later in this process that I first met Robin and offered to help with the marketing of his books. Martin Gordon had organised a stand at the 1993 London Book Fair for Robin's book publishing project, Praxis Institute Press. It was here that Gnosis, as well as titles from the Eastern Orthodox tradition, were officially launched in the UK. On the last day of the exhibition, an elderly man came to the stand, taking a keen interest in the books and how we were getting on. He stayed to talk to us for a while before moving on to visit other stalls. For an elderly man, he possessed great energy and enthusiasm that felt quite infectious. After he left, Martin said the man had been a direct student of both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, and I felt disappointed not to have engaged him in further conversation. I had to leave, as I was travelling up to Scotland later that day. As I walked along Kensington High Street to collect my car, the same man was standing at the bus stop. He spotted me and we greeted each other. The conversation was warm and full of life. I said I was going to Scotland to do some winter climbing. We shared a passion for both Scotland and the mountains. I said I would like to meet him again, and so he invited me to lunch when I was next in London. For me, this was the beginning of a wonderful friendship and an opportunity to hear about a world which I previously had only been able to read about in books. The gentleman in question was Aubrey Wolton, then aged 93, who had first met both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky in Constantinople in 1921.

To describe the nature of our friendship would be beyond the scope of this article, but what impressed me about Aubrey was that throughout the whole time that he knew these great characters and their many collaborators, he maintained working friendships with them all. Also, Aubrey could see things from a much wider perspective, as evidenced in his interest in the publication of Gnosis, believing in the positive role The Work could play for the benefit of society as a whole. He was his own man and knew how to be of service. He never sought any kind of status, position, or authority for himself in The Work. As a result, his name is rarely mentioned in the Fourth Way's broader literature, though careful research online does reveal a few fragmentary glimpses.

Aubrey certainly recognised the importance of Mouravieff's work, as on my visits to his house, I could see that the volumes of Gnosis on his bookshelf were not simply ornaments but were well-thumbed, and he developed a close relationship with both Robin and Lillian. In fact, before Robin's death, Robin bequeathed me the correspondence they maintained with Aubrey during that time. It makes for poignant reading as Aubrey encourages and advises them through periods of discouragement and some of the most challenging stages of the translation. Aubrey also played an important role in contacting the dwindling group of former students of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky who were still alive about Robin’s work and Gnosis. Considering his interest, I once asked Aubrey if he had ever met Mouravieff. This elicited a fascinating reply. He said he and his fellow students knew of Mouravieff's visits and had seen him when living at Lyne in the 1930s, but he never met him. As a result, Mouravieff was something of a mysterious figure, and they asked Ouspensky if they could meet him, but Ouspensky refused their request.

The group of former students who played a supporting role in Gnosis's translation was a wide one. Those I knew of included Annie Lou Stavely and John Lester, whom Robin and Lillian visited in Oregon. Alicia Kenney, Kenneth Walker's secretary, helped fund the book, and Richard Guyatt at the Study Society, with whom Robin remained in close touch and would regularly visit. Aubrey also introduced Robin to another close friend, Ronnie Stennett-Wilson. In another interesting connection, I became friends with Lewis Creed, Beryl Pogson's literary executor. For a short while, I helped Lewis market Beryl Pogson's books before Eureka Editions took on the role in 1995. Lewis and I remained friends, and he introduced me to Bert Sharp, who, like Lewis was a former Pogson student and was in the process of organising the first “All and Everything” conference. Bert was very kind to me and had an encyclopaedic knowledge of all things related to The Work. Unusually, he also had excellent information on and an interest in Mouravieff. He had acquired this information via sources unrelated to Robin's connections. Through this interest, he asked me to invite Robin to come and talk at the first All and Everything conference in 1996.

While Gnosis wasn’t widely known in the English-speaking world, it was in the French. This was partly the result of Mouravieff’s contributions to Synthèses magazine in the 1950s, but he also ran his own groups and a course at Geneva University on esoteric Christianity. As a result, Gnosis achieved quite significant sales when it was published in the 1960s. Despite the fact that his wife Larissa, had to close his Centre for Esoteric Christian Studies (C.E.C.E.) after his death, Mouravieff’s legacy has been sustained in France in more recent times through the work of l’Association Boris Mouravieff. Robin and Lillian maintained close relations with members of l’Association beginning with the translation of Gnosis, and this continued until their deaths. Part of the reason Gnosis wasn’t well known in the English-speaking world was that the translation Mouravieff authorised by Mrs. Lucas of Volume 1 and Manek D’Oncieu of Volumes 2 and 3 hadn’t been published, and very few people had seen it. Mrs. Lucas was the wife of Mouravieff’s secretary, and D’Oncieu was one of his students. D’Oncieu’s translation served as the basis for Robin’s translation of Gnosis 2 and 3 when Dick Wissa left the project following the publication of Gnosis 1. In Dick’s absence, Ted Nottingham assisted Robin with the translation of Gnosis Vol 2. In addition, Robin speculated that there was a reluctance in some quarters to publish Mouravieff because of Mouravieff’s 1958 article published in Synthèses magazine, Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and Fragments of an unknown teaching, which was critical of both Gurdjieff’s teaching methods and character.10

Attending the conference appeared to be an excellent opportunity to introduce Robin's research about the spiritual tradition of Mount Athos and his own role in the publication of Gnosis to others involved or interested in The Work. By 1996 Robin had already moved beyond his role as the translator of Gnosis by writing his own book A Different Christianity about the spiritual tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy, and published in 1995. This book made a detailed study of the methods and practices of Athonite monasticism and provided interesting insights and comparisons to the Fourth Way's psychological method. Robin felt these insights and comparisons might be particularly useful for others at the conference, especially as the Orthodox connection to the Work had been much neglected. He brought his findings in good faith, yet the reception his talk received was decidedly mixed, as the transcripts of the proceedings show. At that time, being young and inexperienced, I had little idea of the politics or factions this work had generated in the decades after Gurdjieff and Ouspensky’s deaths in the late 1940s.

Eighteen months later, Lillian sent me a copy of an article on Mouravieff, which later became a section in a book written by William Patrick Patterson, a one-time student of Lord Pentland, called Taking with the Left Hand. Reading it, I saw one unusual incident that occurred at the conference in a different light. On the second evening, Robin and I ended up being seated for dinner with Patterson and Alick Bartholomew, the original publisher of Jonathan Living Seagull and founder of Gateway Books. Alick and Robin were both larger-than-life characters and sat opposite each other. They got along very well. One might imagine remembering interesting esoteric conversations between these two, but their most memorable exchange was Alick trying to persuade Robin as to the benefits of his latest discovery… Kombucha Tea. Throughout most of the conversation, Patterson, who sat opposite me, was subdued. I had never met him or even heard of him. He must have been aware that I was assisting Robin and had an interest in Gnosis because, at one point, he leaned over to me and whispered. "You don't believe all that stuff about the Fifth Way, do you?" This reference to Mouravieff's contention that a more rapid path of esoteric development can be achieved by two people, a man and a woman working together, was, in the circumstances, bizarre. By framing the question in this way, he clearly already held a negative view of the subject.

Both the article and the subsequent book were hostile towards Mouravieff and Robin's efforts to translate and make Gnosis available. Seemingly having little information on Mouravieff other than what was available in Gnosis and possibly Mouravieff's 1958 Synthèses article, Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, and Fragments of an Unknown Teaching, Patterson created a story around Mouravieff and his relationship with Ouspensky based on his own opinions. It described Mouravieff as having plagiarised and appropriated Ouspensky’s work to portray “The Work” as Orthodox Christian teaching. In that, he also saw him as being devious in his intention. This theme appears as a counter to Gurdjieff’s admission, recounted in Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, and Fragments of an Unknown Teaching, that “maybe I stole it” when discussing the source of “The Work” with Mouravieff. He also cast Robin as a villain because of his role as translator and promoter of Gnosis, ably assisted by his group of devoted Mouravieff "followers." I could only think he was referring to me! He hadn't met anyone else connected with Robin. Certainly, he had no idea of the efforts of the few remaining students of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky to get Gnosis published in English. Reading the transcripts many years later, I concluded that Patterson appeared to believe that the publication of Gnosis, its direct reference to the teachings of the Orthodox Church, and Robin’s contention that the Hesychast Tradition was a key aspect of the psychological components of the “Gurdjieff Work” represented an existential threat to Gurdjieff’s teaching. Ultimately, though, whatever he intended by writing his piece, the effect on Robin and the future of Gnosis was very definite.

Robin, who had come to the conference in good faith to share the fruits of his research, refused to respond. In his heart, he felt it would be impossible. Lillian felt the same. They were probably right, but it seemed very unjust. While Robin did receive support from senior people in “The Work,” such as Ted Nottingham and Richard Smoley, and also Claude Thomas 11, Robin no longer made any efforts towards fostering a relationship with the wider body of this community. Instead, he turned to Athos for succour and, in the coming years, began a long study of Gregory Palamas and his work The Triads, deepening his experiential knowledge of the Hesychast tradition. This resulted in an excellent translation and commentary on The Triads in 2002, which was revised and published in 2016 as Holy Hesychia, the stillness that knows God. For those who wanted to see Gnosis find its place within the pantheon of “Work” literature, they were to be disappointed. It must have been one of the last occasions I met with Aubrey before he died in 1999, and I related these events to him. After I had finished, we sat in silence for a very long time. At the end of the silence, I asked Aubrey, who had been a close friend of Lord Pentland from when they met at Lyne in the 1930s and had subsequently worked together in Washington during the Second World War, if he had ever heard of Patterson or read any of his books. He just shook his head. “No,” he said.

Part III

I realised in the years that followed that I was very naive in arranging Robin’s visit to this conference. The reaction he received was to some degree, understandable. Ever since Gurdjieff died in 1949, his various pupils had gone their own way, forming different groups and organisations. By the mid-1990s, people like Aubrey, Annie Lou Stavely, Dick Guyatt, and John Lester, who had actually been taught or studied directly with Gurdjieff or Ouspensky and helped maintain a unifying thread, were fast disappearing. The All and Everything conference itself was centred on a celebration and study of Gurdjieff’s primary book. This book is noteworthy because it created a whole new language for teaching compared to the one that had originally been transmitted by Gurdjieff to Ouspensky during the period 1915-1918. This new language, even by the time of the first All and Everything conference, had already taken on a life and tradition of its own. People wanted to meet and deepen their knowledge of All and Everything, but by this time, the differences in language had created a deep split between the Ouspenskyites and the Gurdjieffians. The fact that Mouravieff’s Gnosis to some degree reflected that earlier language of The Work immediately put Gnosis on a “lower” level than that of All and Everything, aligning it with Ouspensky’s teaching, which in some “Gurdjieffian” eyes was seen to contain errors. Ouspensky, after all, had left Gurdjieff in 1924 and not received his later “teaching”.

Secondly, it is widely understood by those in The Work that Gurdjieff is the source of the system of teaching presented by Ouspensky. While its lineage may have been drawn from various ancient traditions, the terminology, diagrams, and the meat of the teaching itself, if not Gurdjieff’s sole invention, were at least formulated by Gurdjieff. This is important because any perceived claim that its true source was elsewhere would immediately be treated with suspicion. Again, this was understandable because many different theories as to the source of the System have been put forward over the years. The assumption of some of the audience was that Robin had come to tell them that the Hesychast tradition preserved in the monasteries of Eastern Orthodoxy was the actual source of the system, just as others had claimed it had come from Sufism, Tibetan Buddhism, or other Central Asian and Indian traditions. However, Robin was well aware that the truth of the matter wasn’t quite that simple. There were parallels, but quite clearly, there were important differences that could not be so easily explained.

Robin himself held Gurdjieff in high regard, despite knowing all the contradictions of Gurdjieff’s character. This knowledge did not just come from Mouravieff’s Synthèses article but direct first-hand correspondence with those affected by Gurdjieff’s behaviour, especially with women, and also discussions with former pupils. It has to be said that much of this knowledge is now a matter of public record. However, Robin concluded that Gurdjieff straightened himself out in the last two years of his life. Certainly, the period following Ouspensky’s death, when Gurdjieff received many of his former pupils, was extraordinary and did provide an impetus to the Work that has survived to the present day. He was also convinced that in the last two years of his life, Gurdjieff tried to point some of his pupils towards Orthodoxy and specifically Mount Athos. Hence, he related the story, published in an article in Gnosis Magazine named “The Secret of the Source,” that Gurdjieff told a former student that he should go to Athos and “re-establish” contact with the Tradition.12 He related the story again during the All and Everything conference. It has to be said that the claim was met with scepticism and even hostility by some...

Robin first told me about the story when we first met in the early 1990s; however, he never said who the person was, and it felt wrong to ask. As time went by, I imagined that this former pupil could only be Aubrey, so one day I asked Aubrey if he had ever been to Mount Athos. He said he had and that Gurdjieff had told him to go shortly before he died. He went to Athos with three other senior students, and they spent some time on the Holy Mountain. I asked him if he had found something from which he could work. He said that he hadn’t, so nothing came of the connections he made at that time.

Having always assumed that it was Aubrey whom Robin was talking about, I never discussed it further with him. Then, only recently, I brought the subject up with another colleague who was also friends with Robin and Lillian. He told me that after Robin died in 2014, he had asked Lillian if it was true that Gurdjieff had advised a pupil to go to Mount Athos. “Yes”, she replied, “it was a member of Mrs. Staveley’s group and another man, a Frenchman, Bernard Lemaître, who had drowned shortly afterward”.

Clearly, Aubrey wasn’t the only person to be directed to go. Furthermore, while researching this article, I was surprised to find in the first All and Everything conference proceedings that I had forgotten that Dimitri Peretzi, when asking Robin a question, had said that he and several others had been directed to go to Athos by Lord Pentland. Pentland had given him a list of names to contact when he arrived on the Holy Mountain. Peretzi was surprised that Pentland possessed such a list. Yet the visit had a profound effect on him and another person in the group. This person remained, eventually becoming an Abbot.13

In recent times, more information has become available concerning Ouspensky’s groups at Warwick Gardens and Lyne, but also specifically regarding Father Nikon and the early efforts to translate the Philokalia. Recently, I discovered among Lillian’s papers a short article on Father Nikon by James George, the diplomat and environmental campaigner, and a close friend and disciple of Madame de Salzman, which had been published in his book Asking for the Earth. This fascinating article about how Father Nikon was allowed out of seclusion to visit Gurdjieff and Ouspensky groups in both London and New York is definitive proof that Father Nikon's existence and the connection to monastic Orthodoxy were widely known throughout senior circles of the Work in the 1950s. Gerald Palmer organised the trip and made the necessary arrangements for the visit. George’s article is instructive because it gives a first-hand account of Father Nikon’s use of the Jesus Prayer and George’s own efforts to practise it. It is also important because it shows that Gerald Palmer did not cut off contact with the Gurdjieff Work once he became Orthodox, but continued to foster an interest in Orthodoxy amongst his friends well into the 1950s.

In addition, Nicholas Mabin’s article Evgenia Kadloubovsky 1892-1965, An Appreciation, published in Sobornost in 2023, makes an in-depth study of Madam Kadloubovsky’s life, her role as Ouspensky’s secretary, and as a translator. Perhaps most importantly for students of “The Work”, we can see that both Madam Ouspensky’s and Evgenia’s efforts to translate sections of the Philokalia into English at Lyne and present these translations to groups in the 1930s were the genesis of the series of publications by Palmer and Kadloubovsky in the 1950s, detailed earlier in this article. In addition, Andrew Louth notes Madame Kadloubovsky was almost certainly the primary translator, as Palmer only had limited Russian and worked as editor and “polisher”. The role played by Ouspensky’s groups while not promoted by Metropolitan Kallistos was at least acknowledged in his article quoted earlier, Two British Pilgrims to the Holy Mountain: Gerald Palmer and Philip Sherrard, when he said the following, “He (Palmer) always spoke of his former teacher (Ouspensky) with gratitude and respect. As he told his sister Elizabeth, ‘I received nothing but good from that man’”.

Part IV

On reflection, I can see that Gnosis and also Robin’s work that resulted in his book A Different Christianity, breathed new life and hope into Aubrey when it came to The Work. In the last years of his life, it brought many questions to a close, and I am certain it made sense of Gurdjieff’s suggestion that Aubrey go to Athos.14 The fact that he failed to find anything on his visit circa 1950 proved irrelevant. He met both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky in Constantinople in 1921, joined others at the Prieure in the early 1920s, as a young man assisted John Bennett in the running of the Ouspensky groups in the late 1920s and 30s. He went on to work closely with both Ouspensky and Gurdjieff in the late 1940s and remained close friends with all the disparate groups long after both of them had died. By the late 1980s, he had passed through many other stages, not least the Subud and Idries Shah affairs. When Gnosis appeared, he immediately understood its importance. His aim and those of the former students were to help make Mouravieff’s Gnosis available, because in their view it represented a “more complete record”, which they had only received in part. When it came to playing his part, it appeared to me that in those last years, Aubrey possessed a definite clairvoyance, and over a lifetime of experience had learned how to apply it. This shines through in his letters as he encourages Robin and Lillian in their task. He says in a letter dated 17th June 1992:

“It was very largely due to the publication of the Gurdjieff and Ouspensky books – nearly fifty years ago – that the outline of this traditional teaching was made available to a wide public and kept alive the interest of a new generation. The publication of this more complete record based on Mouravieff’s work seems to me to have been timed to meet an altogether new situation in human affairs and those whose efforts preserved the tradition for half a century can now see how this made it possible for this new impulse to be given... Mouravieff wrote that he knew Ouspensky and Gurdjieff in the 1930’s. I knew this was so – but I never met him.”

In this regard, Aubrey knew how important it was for Robin to complete his task as well as the nature of the difficulties he would face. In another letter dated 11th December 1991, he said this:

“One of the great difficulties here, as I may have told you – is the great number of individuals and groups of people with very different views who continue to discuss the past and think very little of the future. You’ve no doubt got plenty of people like that – but at this vital moment, I think it is better just to politely avoid them. You have an infinitely greater power behind you – and it needs your quiet and uninterrupted attention to complete its work.”

As to the application of this “infinitely greater power,” he knew how the opposition would arise and when those moments of crisis and discouragement would inevitably come, and how that power could be used to mount an effective opposition:

“I know that the handling of all this material, in circumstances which have been very difficult, has been for you both painful and often bewildering – but if you manage, with this new arrangement with “The Great Tradition” to achieve the aim you were set, then it will have been a classic instance of how the laws, under which we all have to exist, can only be circumvented by complete determination and conviction. It may have seemed as if I was being discouraging when I emphasised that such work can only be carried out with a good deal of pain and suffering – and with frequent frustration which often seems to come from people who you have expected to be helpful. These kinds of obstacles may still get in your way, and you must still be prepared to stick to your direction with the utmost determination.”

Aubrey would say to Robin, “Your future lies in America. It is to the Americans your message will be heard”. Aubrey would express his view of Robin’s future to me, also. I could see the truth of it, but for a different reason. In America, Robin would be listened to and could fill a room at the New York Open Centre, whereas in England, I could only manage to get a handful to turn up for Robin’s talks in the basement of Watkins Bookshop in London.

As for Robin, he couldn’t take this last piece of advice. He was struggling with his health and diabetes, but also a longing for England. He and Lillian left America in 1995 to return to the UK and his work, his mission, most definitely struggled as a result. These struggles were further compounded by the rejection he felt following the “All and Everything” conference. Yet despite all the difficulties Robin faced, he did complete the translation and publication of Gnosis. He also translated key sections of the Mouravieff archive, Mouravieff’s course notes, published articles, and his autobiographical work Initiation, which contains information as to how Mouravieff originally came to know about the body of work which became known as The Work. This body of work is publicly available through the University of Geneva Library and is available for a future generation to make use of.

Also, and most importantly for Robin, he never wavered from his dedication and love of the teachings he discovered first through Metropolitan Anthony at Ennismore Gardens and subsequently on Mount Athos.

In A Different Christianity, as well as his beautifully observed book Views from Mount Athos, Robin managed to fashion a comprehensive bridge between the complex theological language of the Eastern Fathers into one that could be understood and applied on a practical level for the intellectualised Western seeker. What is more, he could bring the seeker to the point where what would otherwise remain external and intellectual (Greek: dianoia)15 could become internal and noetic (Greek: nous)15. This is an essential requirement if we are to take this practical and lived teaching through to the actual experience of God. A person can only communicate this if they have gone through the process. I am certain this was why he was given the honour of being a "synergatis", a fellow worker and equal of the monks at Grigoriou. This designation, as a “fellow-worker,” based on the language of St. Paul, is highly unusual, but Robin kept a letter from the Gregoriou attesting to this honour. 16 It is also the reason why A Different Christianity has brought many people, both lay and Orthodox, to a deeper understanding of the essential nature of the spiritual tradition of the Eastern Church.

NOTES

1Gnosis, Study and Commentaries on the Esoteric Tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy by Boris Mouravieff published in English by Praxis Institute Press. Volume One 1989, Volume 2 1992, Volume Three 1993. Originally published in French by Les Editions du Vieux Colombier, Paris 1961, then by Les Editions de la Baconniere 1972.

2 Lillian Amis (nee Delevoryas). The artist and surface pattern designer

3 “The Gurdjieff Work”. Gurdjieff was a man of Armenian Greek descent. He brought to the West a psycho-spiritual teaching he acquired from a young age while living and travelling through what is now Eastern Turkey, Armenia, Georgia, and central Asia, including Tibet. He transmitted this teaching he called “The System,” to the writer and philosopher P.D. Ouspensky and others in the period 1915-18. A summary of this teaching can be found in Ouspensky’s book In Search of the Miraculous. The teaching can be divided into two essential elements. A psychological, inner or personal aspect called “The Work” and a cosmological aspect, which when combined with “The Work” can be called “The System”. Ouspensky, who was already a well-known author in his own right broke from Gurdjieff in the early 1920s and continued to teach in London, while Gurdjieff settled in Paris and reformulated the teaching. This reformulation is outlined in Gurdjieff’s book All and Everything.

4 Rod Thorn’s interesting biography of Robin’s early years in London in the 1950s and 1960s shows him to have been a dynamic character as well as influential in a number of fields most notably as part of the group who brought Kabbalah out of aristocratic and wealthy circles to a wider audience.

5 Further reading: Two British Pilgrims to the Holy Mountain: Gerald Palmer and Philip Sherrard. Also, the introductory booklet written by Lillian Delevoryas for the 2016 reissue of Readings from the Philokalia on Prayer of the Heart (Audiobook). This fascinating piece details the connection between Father Nikon and the Kadloubovsky family.

Also, a detailed study of these events is made in The Way of an English Pilgrim: Gerald Palmer’s Lifelong Anthonite Pilgrimage by Christopher D L Johnson.

6 I wondered for a long time whether to introduce this fact because it would be unbelievable for many who have an interest in “The Work,” and it seems certain Ouspensky hid it from his pupils. Yet, for me at least, it does make sense of certain contradictions in Ouspensky’s work and his character. On the one hand, he recognises both the importance of texts like The Philokalia and places like Mount Athos, and yet his students are discouraged from approaching them because, for Ouspensky, they represent another way, the Way of the Monk. This approach must have been personal to Ouspensky because it is quite clear from In Search of the Miraculous that Gurdjieff did not discourage such interest in Ouspensky. It is well known that Ouspensky maintained a clear division between the intellectual rigour of “The System” and refused any talk of God or religion. For Ouspensky, these two aspects could not be mixed. Yet the revelation that he himself possessed a religious aspect raises a big question. We cannot know whether he went to the Liturgy for duty, tradition’s sake, or to feed something within himself. The fact is, though, he was not prepared to share this with his students. Interestingly, Francis Roles’s in an interview, described him as a deeply religious man. It has to be said that Gurdjieff took a similar stance with his pupils, though he applied it differently. When asked by Mouravieff, “I find the System the basic Christian doctrine?” Gurdjieff had replied, “Yes, but they don’t understand that at all.” Well, yes, but how is that audience going to begin to understand if it isn’t even discussed? Having been Orthodox for many years and having made my own observations, I wonder if there wasn’t a deeper cultural or racial issue at the heart of this. Could it be that a man like Ouspensky thought a person could not be truly Orthodox or even understand its nature if one is not Russian or even Greek, for that matter? Likewise, could it be that a religion becomes so culturally integrated into a society that it becomes almost impossible for its adherents to express its nature in separation from their cultural/national identity? In the end, it has taken a wide range of Western-born authors across the English-speaking world to express clearly that a lived Orthodoxy is not defined by nation or nationality but has a universal aspect. This was something that both Ouspensky and Gurdjieff shied away from discussing with anyone until very late in their lives.

7 Johnson C. D. L. The Mystical Mundane, Fr. Nikon Of Karoulia’s Letters To Gerald Palmer, Orthodox Monasticism Past and Present, Edited by McGuckin J. A., Sophia Studies in Orthodox Theology Vol. 8. This confirms Father Nikon’s membership of the Theosophical Society.

8 O’Farrell, M., Boris Mouravieff: A Revised Biography. (publication to be announced)

Recent research also shows that Mouravieff and his family were well acquainted with the charismatic founder of the St Petersburg section of the Theosophical Society Anna Kamenskaya. Mouravieff who escaped France in 1944 followed in her footsteps to lecture at Geneva University after the Second World War.

9 This quote is given in an article Gerald Palmer, the Philokalia, and the Holy Mountain by Bishop Kallistos on Gerald Palmer’s relationship with Mount Athos from Ouspensky’s death: https://docplayer.net/65399229-Friends-of-mount-athos-annual-report.html

10 This article was used as a source of information about Mouravieff by James Webb in his book, The Harmonious Circle. It was perhaps the first public indication of Mouravieff’s existence in the English-speaking world. The book concentrated on aspects of Mouravieff’s relationship with Ouspensky and Gurdjieff, which is unfortunate because the full article wasn’t available in English, and though Mouravieff is circumspect, it contains a number of very important indications for the seeker as to the origin of “The System”. While Gurdjieff’s character and teaching methods were one aspect of Mouravieff’s concern, there was perhaps a greater one. When Mouravieff asked Gurdjieff, “Where did he get 'The System’?” he answered, “Maybe I stole it”. Gurdjieff never revealed his sources, but because of the way he outlined the nature of his search in Meetings with Remarkable Men, the idea that “The System” was not Gurdjieff’s has always been a central question for those in interested in The Work.

11 Claude Thomas, one of the directors of l’Association Boris Mouravieff wrote a comprehensive rebuttal of Patterson’s original article and Ted Nottingham translated it into English. Appendix 1 of – Wisdom of the Fourth Way (Theosis Books 2011; ISBN 978-0-9837697-0-5) (author; Ted Nottingham)

12 Also see A Different Christianity by Robin Amis, Praxis Institute Press, 2005, p. 347-8.

13 All and Everything Proceedings ’96. Copies can be purchased here: https://aandeconference.org/shop/

14 Why did Gurdjieff make the recommendation for some of his senior pupils to go to Athos, and likewise, why was Ouspensky keen to see the translation into English of The Philokalia? If one studies both the Hesychast tradition and “The Work” in enough depth, the parallels of certain aspects of the teaching make the answer obvious enough. However, there is another reason, more subtle but understood by the authors of the “System”. It is remarkable to consider that today, Athos and a few other Orthodox monasteries remain spiritual bastions; a very real legacy of the ancient world that has survived into a modern world that, over the last 100 years, has seen the inner traditions of the other Great Religions suffer shocking losses, most notably in Islam and Buddhism. Ouspensky always stated we live in an age where “Schools” are disappearing. He has been proved right.17 Also, both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky personally witnessed the onset of the spiritual and cultural destruction of vast swathes of Asia from what is now Turkey, the Middle East, through to Iran, and all across central Asia. As we see by events occurring to the Uyghur peoples today, this process continues. Without doubt, both men were aware of these destructive forces. In reality, Gurdjieff, particularly on his father’s side, represented an ancient lineage from a time now long gone, and where those who were Awake were not divided by religion but recognised their common heritage and humanity. As a consequence of these events, it is incumbent on all of us today who hear the call to recognise the great responsibility we carry; to take the Tradition bequeathed to us to a new age, where the language it speaks can be heard by a new generation wanting to hear it. To achieve this, we will not only have to work together but also understand both our true nature and The Tradition itself, as well as live it in the World.18

15 Dianoia and 15 Nous. In the English translation of The Philokalia, the Greek term “Nous” is translated as “Intellect”. To the untrained eye, this could easily cause confusion as intellect in Western usage is closely associated with the idea of reason/reasoning i.e. the discursive, conceptualising and logical faculty in man (Greek: dianoia). The following paragraph is an extract from the glossary of the English translation of The Philokalia that clearly defines the difference between these two concepts. It would not be outlandish to argue that this difference is at the heart of the division between the Western intellectual tradition, including Western Christianity, and the spiritual tradition of the Eastern Church. The cultural root of this difference is very ancient. For example, there is an observable difference between the writings of Plato and his pupil Aristotle in this regard.

“...“Nous” (which is translated as Intellect in The Philokalia): The highest faculty in man, through which, provided it is purified, he knows God or the inner essences or principles of created things by means of direct apprehension or spiritual perception. Unlike dianoia or reason from which it must be carefully distinguished, the nous does not function by formulating abstract concepts and then arguing on this basis to a conclusion reached through deductive reasoning, but it understands divine truth by means of immediate experience, intuition, or “simple cognition” (the term used by Isaac the Syrian). The nous dwells in the “depths of the soul” and constitutes the innermost aspect of the heart (St. Diadochus). The nous is the organ of contemplation, “the eye of the heart.” The Philokalia, The Complete Text (published by Faber and Faber).

Comment: To avoid this confusion of terms when reading The Philokalia and to train our western educated mind as to the nature of the Eastern understanding of the term, it is fruitful, in the beginning, to stop and make a mental translation of both the term ‘intellect’ and the localised text, as well as consider the essential difference of meaning between ‘intellect’ and ‘nous’ in relation to the text being examined.

16 A copy of the letter can be found on the Praxis Research website, www.praxisresearch.net. Robin’s efforts to encourage seekers to develop an experiential understanding of the teaching of the Fathers as well as books such as Gnosis are continued today by the members of Praxis Research. This involves hosting online study meetings, retreats, and maintenance of the Praxis website. Members also collaborate on research projects.

17 By “schools,” Ouspensky meant schools for spiritual teaching and learning. These could be monasteries, but also other types of schools where esoteric knowledge is carried or preserved, e.g., the Cathedral builders of the Middle Ages. (See A New Model of the Universe by P.D. Ouspensky, the chapter entitled, In Search of the Miraculous, for other examples).

18 Ephesians 14-19. "For this reason, I kneel before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth derives its name. I pray that out of his glorious riches he may strengthen you with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith. And I pray that you, being rooted and established in Love, may have power, together with all the Lord’s holy people, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge—that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God."

References

http://www.soho-tree.com/blog/robin-amis-ouspensky-and-esoteric-christianity

https://www.gurdjieff-internet.com/article_details.php?ID=383&W=1

https://www.josephazize.com/2017/08/12/from-ouspensky-to-the-philokalia/

Boris Mouravieff, Wikipedia

Robin Amis, Wikipedia

Lillian Delevoryas Wikipedia

Mount Athos, Wikipedia

"The 'Mystical Mundane' in Fr. Nikon of Karoulia's Letters to Gerald Palmer," in Orthodox Monasticism Past and Present: Sophia Studies in Orthodox Theology Vol. 8 (Theotokos Press, 2014)

Meetings with Remarkable Men, G.I. Gurdjieff, Penguin/Arkana

A Record of Meetings, PD Ouspensky, Penguin/Arkana

The Fourth Way, PD Ouspensky, Penguin/Arkana

The Philokalia, The Complete Text, Faber and Faber

The Way of a Pilgrim, edited by Andrew Louth, Penguin Classics

The Heart of Salvation by St Theophan the Recluse, translated by Robin Amis, Praxis Institute Press

Readings from the Philokalia on Prayer of the Heart, CD Audiotape, G.E.H. Palmer. Praxis Institute Press

A New Model of the Universe, PD Ouspensky, Various

The Psychology and Cosmology of Man’s Possible Evolution, PD Ouspensky, Various

A Different Christianity, by Robin Amis, Praxis Institute Press

Views from Mount Athos, by Robin Amis, Praxis Institute Press

Synthèses magazine article: Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and Fragments of an unknown teaching by Boris Mouravieff, Praxis Institute Press

Taking with the Left Hand, William Patterson, Arete Communications

The Triads, St Gregory Palamas, translator Robin Amis, Praxis Institute Press

Gnosis Magazine, Issue 20, article “Mouravieff and The Secret of the Source” by Robin Amis 1991